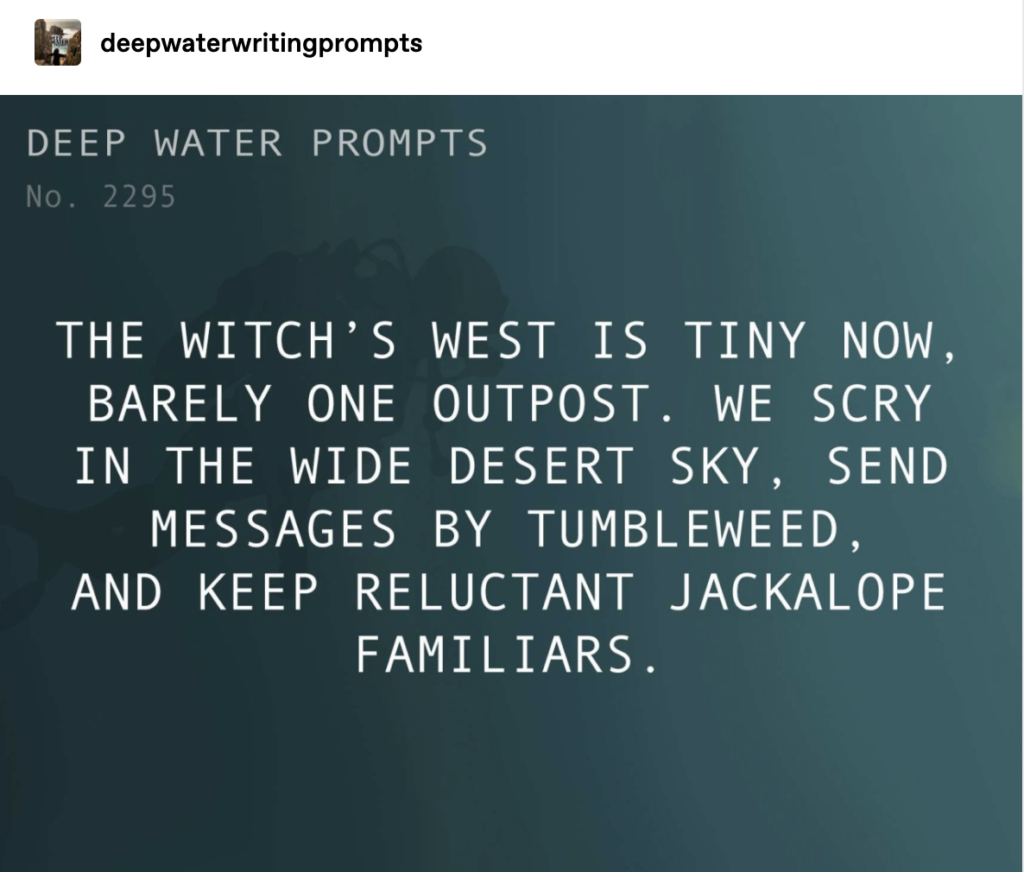

The turn of the century invents the steam train, but the turn of the millennium invented Witches. They’re out of fashion now. Black doesn’t do well in the wild west, after all. It’s shades of white and brown nowadays. Maybe some red if the light hits it right. The world has changed, but witches have stubbornly stayed the same.

Samantha Bonda is a Witch, one of the old kind before the automobile and the factory. She’s old and mean and she lives in a postal station in somewhere called ‘Nevada’ and she has a Jackalope familiar and sends messages by tumbleweed. Or so the newspapers say.

So Shelly is surprised to get her summons via post. She even had to pay the fee herself with her meagre spending money. She’s almost fifteen now and her Pa’s looking for a nice husband for her, so Samantha Bonda’s message is a welcome alternative.

“No daughter of mine is gonna be witch,” Pa tells her, tearing the telegram in half and hurling it into the hearth. Pa refuses to buy electricity unless the county will pay for it, and the county doesn’t give a hoot about the boonies, so it’s candles and firewood for them. He grabs his pipe and goes outside. Ma looks calmly at Sam, then shrugs.

“Be a witch,” she says simply, “can’t be scarier than marriage.”

Their life isn’t easy, but Shelly thinks that might be a little harsh.

And then Pa introduces her to Tobias. Tobias likes her.

She begs money off of Alice at the farmer’s market, and goes two words over the maximum and has to beg money from her mother too the next day.

But she gets that reply sent.

Tobias brings her daisies. They’re perfectly nice, and he seems fine, if she can look past the fact that he wears a full beard and looks at her too long and too intensely. She is polite when he visits, and her Pa is always in the room with them. So it’s not… terrible.

Ma insists on buying her a new dress to see Tobias at the carnival coming into town, and her father grits his teeth and hands over the money for it, as well as a little extra for a hair ribbon. Ma gives Shelly her pearls to wear. Tells her to bring them so they can match them to the dress.

They shop for the nice dress, but Ma doesn’t let them tailor it. Says it’s too expensive. Tells them Shelly’ll wear her nice new dress out of the store. The dress goes beautifully with Ma’s pearls. Ma tells her so, and there are tears in her eyes.

“You’re all I’ve got, Shelly,” she whispers as they leave the shop.

Then Ma just. Stops. She stands there, jaw tight, eyes miles away. Shelly hasn’t seen her Ma like that before.

“Come on then, girl.” Ma takes Shelly’s arm, a little too hard. Bony fingers gripping enough that Shelly almost says something about it. Except the line of Ma’s jaw looks like it would cut her deep.

She holds her tongue.

They go all the way to the train depot. To the place where the big steamers pull huge loads of cargo and people ever west.

“Go,” Ma says, and shoves the rest of the money and her own purse into Shelly’s hands. “Go find that Bonda woman and… be a witch.”

Shelly stands there holding the purse. She and Ma haven’t seen eye-to-eye ever. Ma is too old world and Shelly is too new. Shelly likes to talk about traveling. Likes horses, and reading about international conflicts. She likes talking to the boys more than trying to earn their favors. Her friends are all wild children. She likes arguing with the newspaper articles and playing kick the can. She made flower crowns for the boys in the neighborhood and nobody thought anything of it.

Ma let her father marry her to Pa and made it work. She takes pride in that. She endures, and she persists, and she calls that strength.

The new world wants women like Shelly to be strong. The old world wants women to be strong like Ma.

“I already sent her a post,” Shelly admits, “I asked her to come pick me up. Or- or pay for my ticket on the train.”

“Unfilial child,” Ma says, and sounds fond. “Then play the damsel card. Tell the conductor that you’re meeting someone in Nevada and they’ll be paying your way. Give him all the money before you get there.” She kisses Shelly on the forehead, gently cradles her own pearls on Shelly’s throat. “Take care of yourself,” she whispers.

“What about you?” Shelly never imagined she’d want to take Ma with her. Never imagined a world where she didn’t turn and run. But Ma smiles. She shakes her head.

“If I go he’ll follow. But if you go and I stay…” She shrugs. “Til death do us part is a promise, honey.” She smiles an old tired smile, “one you haven’t made yet.”

She leans in and kisses both Shelly’s cheeks.

“Go be a witch,” she whispers. “You’d still be a witch here, even if I didn’t send you.”

“I’ll pay for the lady’s ticket to Witch Hollow,” a male voice says in a stately accent, and both Shelly and Ma jump in surprise. The man is well appointed in a three piece suit. He carries a cane made of ash, polished within an inch of its life. The handle is the head of a pointer dog, and a pointer dog who must have sat as the model sits at his feet.

“Ambrose Lucien Belfast,” he introduces himself, tipping his hat. “Will be on my way to Witch’s Hollow myself. Picking up something in the city first.” He looks thoughtfully at Ma. “I could use a local’s advice. We’ll call it a trade. I buy the girl passage, and you show me the city.”

“Sir I am married,” Ma explains, amused.

“Oh ma’am so am I.” He raises his left hand, which has a ring. Non traditional and gold, braided into a solid band. Ma looks mollified. “I mean no disrespect madame. In fact I would love to meet your husband.”

Shelly isn’t sure, but that ‘love’ sounds a bit sinister. And as he says it she sees the dog curl its lip in a small snarl.

“Off you go,” Ambrose hands Shelly a ticket, tips his hat again. “Tell ol’ miss Sammy I’ll be by at the turn of the season for the rattlesnake harvest. Tell her to keep that rabbit of hers in line.” He winks, then taps his cane twice on the cement.

“Now ma’am.” He turns away from Shelly without another word, the ticket in her right hand, a bag she doesn’t remember packing in her left. She watches Ma splutter a little as the man uses his cane and dog to herd her away from the platform. She hears him in the distance say “now ma’am if your husband were, say, a dog or a cat… what kind would he be?”

And the crowd swallows them.

“Witches,” a voice says behind her derisively, and the conductor is taking tickets, shaking his head in disapproval. “We’re lucky there’s only two left in the world.”

Shelly hands him her ticket for punching. She swallows. “Two?”

“Yep. That old man back there-” a gesture in the direction Ma went with Mr. Belfast, “he’s married to some old heiress kook in Nevada. They’re filthy rich though. Gotta be witchcraft.” He grimaces a smile at Shelly. “But never you mind that.” He punches her ticket, then does a doubletake at her destination. He frowns at her. “You keep an eye out for witches in this part of the world.” He waves the ticket at her until she takes it back.

“I will sir,” Shelly smiles, and means it. “I’ll keep a much sharper eye than before. Never know what you might see.”

She steps onto the train and finds a seat by the window to watch her former life pull away in a cloud of steam and the shriek of the whistle. She looks at each person who watches the train go. She notices the way some smile, the way some make eye contact with her for no reason. The way some don’t even seem to be watching the train for any one person specifically.

There’s only one Witch left in the world.

Or so the newspaper says.

But Shelly loves arguing with the newspapers and proving people wrong. She thinks maybe, just maybe, Ma will come visit her sometime soon and bring Pa with her, in whatever form that takes.